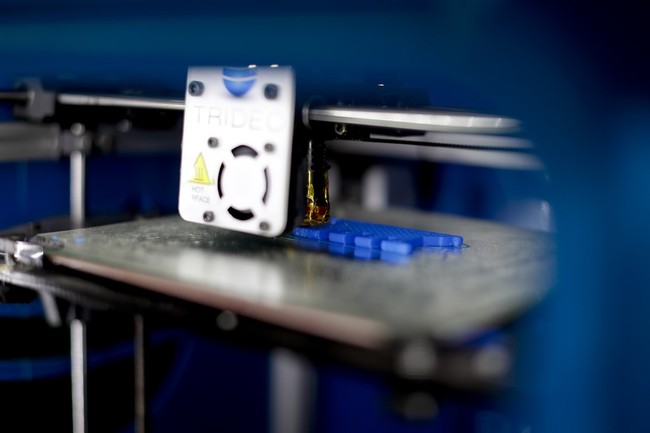

The 3D printer industry and the gun world have an overlap, but not necessarily an intentional one. A lot of people in the 3D printing world aren’t exactly into guns, and while there are many others who are, the truth is that these printers can be used by a lot of different people with a lot of different goals.

That’s kind of what’s cool about them.

But people like Manhattan DA Alvin Bragg, to say nothing of lawmakers in other anti-gun states, think that the government can force 3D printer manufacturers to include technology that will prevent anyone from making their own firearms with these devices.

Never mind that there are only a handful of states that have any bans on such guns, and even in some of those, as long as you follow particular steps, it may still be legal.

However, as is far too typical of activist politicians, they’re saying companies can and should do a thing, without actually understanding the technology.

Those who do understand it seem to have a different view.

As US lawmakers consider bills that would require 3D printers to detect and block the production of firearm components, longtime 3D printing policy expert Michael Weinberg once weighed in again on a debate he has been part of for more than a decade.

The OSHWA board member’s objection is not to gun control itself. Instead, he argues that embedding firearm screening requirements into 3D printers overlooks key technical realities.

Early experiments in 3D printing firearm components began drawing national headlines in 2012. Even then, Weinberg urged policymakers to step back and ask whether 3D printing truly represented a new threat.

Hobbyists had already been using CNC machines and other automated tools to manufacture firearms at home. The arrival of consumer 3D printers did not create home gunmaking, the policy expert argued at the time. It simply made the activity more visible and easier to discuss.

That distinction continues to shape his analysis today. In responding to the proposed screening mandates, Weinberg contends that focusing regulatory energy on the 3D printer itself risks confusing a tool with the behavior policymakers are attempting to address. Laws should target harmful conduct or regulated objects, in his view, rather than the general-purpose devices capable of producing them.

Now, this is something I agree with completely.

After all, P.A. Luty published a book on how to make a submachine gun in your garage with hardware store supplies. No one is pushing to ban rivet guns, welders, or anything of the sort. No one is looking to ban home-based CNC machines, save those developed expressly to make gun components, nor is there any push to restrict home lathes.

Somehow making it so 3D printers can’t make gun components won’t stop people from making guns. At best, it’ll just push them to find alternate ways.

No, they hadn’t before, but that was because the media didn’t bring everyone’s attention as to how this thing could be done. That genie is out of the bottle, though, and so it’s entirely likely that if criminals’ printers won’t do what they want them to do, they’ll just find a Plan “B” and move on.

Then we have the technical issues mentioned above.

At the heart of his criticism is the technical feasibility of printer-based detection. Identifying firearm components based solely on a 3D file’s geometry is far more complicated than it may sound. Mechanical parts often resemble one another.

A component used in a firearm can look strikingly similar to a part intended for a door hinge, a tool housing, or another entirely benign application. Even sophisticated engineering software cannot reliably determine a part’s intended purpose simply by analyzing its shape.

The OSHWA member notes that one possible approach would rely on advanced algorithms capable of analyzing each file before printing begins. Yet most consumer-grade 3D printers lack the computational power to run that level of analysis locally. Moving the task to remote servers would require constant internet connectivity, a significant shift for devices that are frequently used offline.

Such an approach would also raise questions about who maintains the detection database, how updates are distributed, and what privacy safeguards would be in place.

Other approaches rely on matching files against a database of known gun components. Digital matching systems are fragile. Even minor alterations to a model can change its digital signature without affecting its function. A small adjustment to a dimension or the addition of cosmetic geometry could allow a file to bypass blacklist detection entirely. For users intentionally attempting to evade restrictions, modifying a model in this way would not be especially difficult.

This doesn’t even get into people jailbreaking their printers so that they can bypass all of this total BS.

See, the problem is that the people pushing this kind of thing don’t actually know enough about guns or 3D printers to realize the limitations. This isn’t uncommon, as we’ve seen it time and time again. Politicians decide to lay down the law, literally, that something will meet a certain technical marker by a certain time, and then are shocked to learn that it completely upends the industry in question.

CAFE standards, for example, killed the muscle car and are the reason why full-size pickup trucks are the monsters they are today. Few expected that to happen when they passed these technical limits, yet here we are, 50 years later, still dealing with that bit of stupid.

3D printers are amazing devices. I seriously need to finally bite the bullet and get one, not just to make my own firearms, but also because there are so many different things I can just make for the house, the workshop, or just for fun and games.

But because they’re used for so many different things, it’s impossible for the technical dreams of anti-gunners to effectively work without creating a whole lot more problems than they’re theoretically intended to solve.

And none of that would stop bad people from deciding that, since they can’t make a Glock clone on their printer, they might as well build submachine guns from the hardware store instead.

Tell me how that would make our inner cities safer?

I’ll wait.

Editor’s Note: President Trump and Republicans across the country are doing everything they can to protect our Second Amendment rights and right to self-defense.

Help us continue to report on their efforts and legislative successes. Join Bearing Arms VIP and use promo code FIGHT to get 60% off your VIP membership.

Read the full article here