The final flurry of U.S. Supreme Court rulings at the end of June brought several highly positive developments and one major disappointment. Multiple decisions curtailed the power of the federal government’s executive agencies, a much-needed corrective that begins a dismantling of the unconstitutional federal regulatory state.

Even more importantly, the rulings laid the groundwork for a restoration of the nation’s constitutional order to be developed much further in future cases.

‘Courts interpret statutes, no matter the context, based on the traditional tools of statutory construction, not individual policy preferences.’ We’ll see about that.

This includes reestablishing the separation of powers among the three branches of the federal government and the states’ authority over police powers and other matters the Constitution does not explicitly assign to the national government. There is much more work to be done on the latter, but this session’s decisions are a good start.

In a decision written by Chief Justice John Roberts, the court ruled the Securities and Exchange Commission cannot use agency proceedings to prosecute people for fraud. Such cases must be decided in federal courts, the justices ruled in a 6-3 vote. Use of agency proceedings violates people’s Seventh Amendment right to a jury trial, the court said.

The decision will probably extend to other regulatory agencies and enforcement mechanisms. I agree with Justice Sonia Sotomayor’s dissent that the ruling is “a massive sea change” and “the constitutionality of hundreds of statutes may now be in peril, and dozens of agencies could be stripped of their power to enforce laws enacted by Congress.” Sotomayor and the other dissenters argue that the dismantling of the regulatory state would be a very bad outcome. On the contrary, it would be extremely beneficial to the American people. Even more importantly, law enforcement without a trial is unconstitutional and profoundly anti-American.

In another 6-3 decision written by Roberts, the court ruled against prosecution of January 6 defendants for obstruction of justice under a law meant to stop people from destroying documents or otherwise tampering with evidence in criminal investigations. The majority recognized that the law was never intended to apply to every conceivable “obstruction” of “an official proceeding.” Meanwhile, two of the four charges in Special Counsel Jack Smith’s case against Donald Trump are based on this statute.

In dissent, Justice Amy Coney Barrett argued that “statutes often go further than the problem that inspired them, and under the rules of statutory interpretation, we stick to the text anyway.” Such expansive interpretation of federal laws is judicial activism, plain and simple, and has been causing trouble for decades. Now, the justices argue regularly over the texts of the laws and the Constitution in the cases before them, a position known as textualism. That is a great improvement from the court’s many decades of activism.

Reining in activism

In a similar fashion, the court found in Snyder v. United States the prosecution of state and local officials for bribery under federal law is wrong because that authority belongs to the states. The states have the “prerogative to regulate the permissible scope of interactions between state officials and their constituents,” Justice Brett Kavanaugh wrote for the majority. This decision is an important affirmation of states’ authority to use their police powers and a welcome limitation on the federal government.

In Grants Pass v. Johnson, the justices voted 6-3 to strike down a lower court’s ruling that a city could not fine or imprison people for violating public-camping ordinances if there are more homeless people than shelter beds “practically available” to them. “The enforcement of generally applicable laws regulating camping on public property does not constitute ‘cruel and unusual punishment’ prohibited by the Eighth Amendment,” the court ruled.

In addition, although the cruel and unusual punishment clause of the Eighth Amendment “prohibits certain methods of punishment a government may impose after a criminal conviction … it does not impose [any] substantive limits on what conduct a state may criminalize.” For decades, the Supreme Court had been constricting the authority of states and local governments while expanding the reach of the federal government. The Grants Pass decision is a welcome reversal of that unconstitutional habit of judicial activism, restoring to states their full range of police powers.

Good riddance to Chevron deference

Finally, in a long-awaited decision, in Loper v. Raimondo the court removed federal agencies’ permission to craft regulations as they see fit provided that their interpretations of ambiguously worded congressional legislation are not embarrassingly unreasonable. Federal regulators have run wild for four decades under this doctrine, known as Chevron deference after a 1984 Supreme Court ruling, though the practice originated in the New Deal era.

The Chevron decision upended the constitutional order and promoted the massive expansion of the regulatory state. Members of Congress passed laws larded with generalities they could rely on the permanent bureaucracy to transform into greater government power while distancing the legislators from responsibility for those decisions.

The court’s decision to undo that harm in Loper is sweeping and unambiguous: “The Administrative Procedure Act requires courts to exercise their independent judgment in deciding whether an agency has acted within its statutory authority, and courts may not defer to an agency interpretation of the law simply because a statute is ambiguous; Chevron is overruled.”

Writing for the 6-2 majority (Ketanji Brown Jackson having recused herself), Roberts flatly stated Chevron does not make sense and wrongly limits courts’ authority to decide on the legality of executive branch actions.

“Chevron cannot be reconciled with the APA by presuming that statutory ambiguities are implicit delegations to agencies,” the chief justice wrote. “That presumption does not approximate reality. A statutory ambiguity does not necessarily reflect a congressional intent that an agency, as opposed to a court, resolve the resulting interpretive question.”

Resolving statutory ambiguities is, in fact, the courts’ responsibility and area of expertise, Roberts noted: “Perhaps most fundamentally, Chevron’s presumption is misguided because agencies have no special competence in resolving statutory ambiguities. Courts do. The Framers anticipated that courts would often confront statutory ambiguities and expected that courts would resolve them by exercising independent legal judgment.”

The court’s decision to strike down Chevron deference does not encourage legislation from the bench, Roberts argued: “Courts interpret statutes, no matter the context, based on the traditional tools of statutory construction, not individual policy preferences.” We’ll see about that. Chevron deference arose as a way of keeping courts from making absurd reinterpretations of federal laws. The Supreme Court made the right decision in ending it, however, as it is indeed the judiciary’s job to make those mistakes if anybody is going to do so.

A First Amendment setback

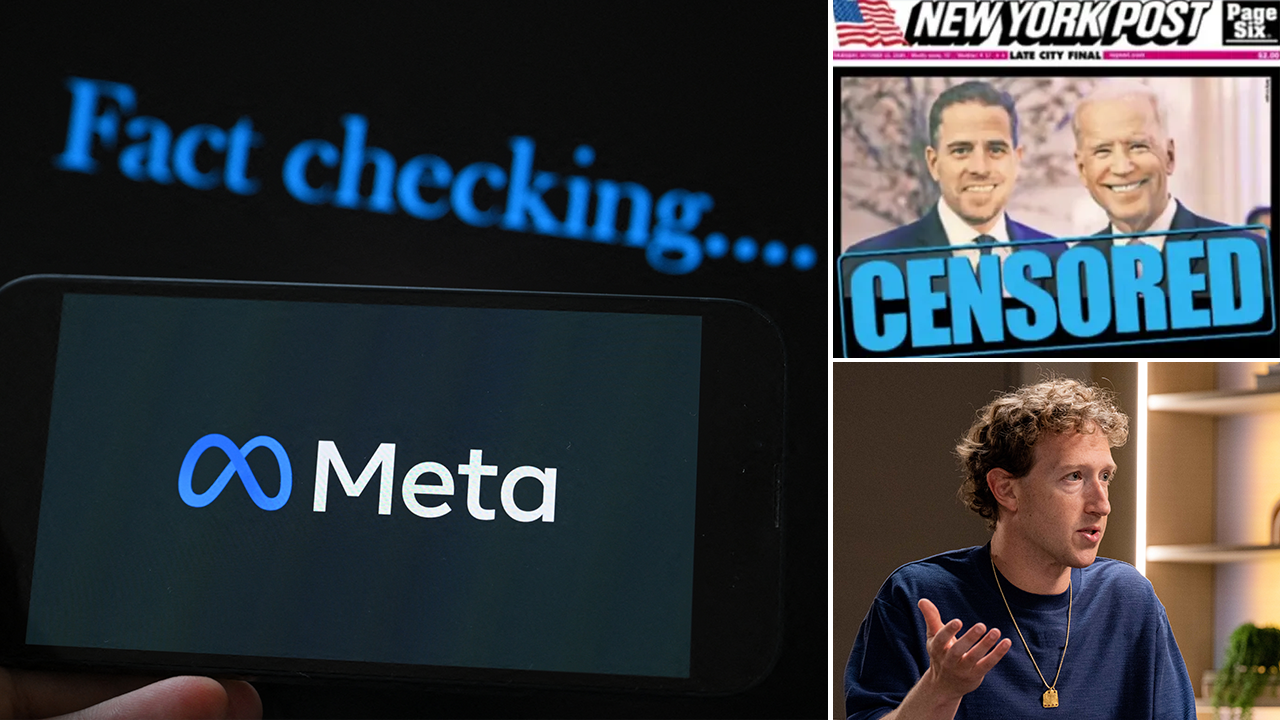

Unfortunately, not all the court’s final-week decisions were decided as sensibly as these. In Murthy v. Missouri, the court gave the government permission to threaten, cajole, and bribe media organizations into supporting the president’s re-election campaign by suppressing bad news about the president and quashing readers’ and posters’ comments critical of Biden.

Instead of making a judgment on the facts of the case, which centered on the federal government’s actions, the court’s majority decided that the plaintiffs failed to “demonstrate a substantial risk that, in the near future, they will suffer an injury that is traceable to a Government defendant and redressable by the injunction they seek.”

The decision indicates the plaintiffs could sue the media organizations for damages for past actions, though of course the lawsuit was aimed at alleged Biden administration wrongs. The majority refused to stop the Biden administration now because the trial courts did not identify enough evidence to prove to their satisfaction that Biden’s team would pressure media organizations to do the same thing again this time around.

The dissent written by Justice Samuel Alito (with Thomas and Gorsuch concurring) argued that the plaintiffs provided plenty of evidence showing the Biden administration’s actions harmed the defendants.

“For months in 2021 and 2022, a coterie of officials at the highest levels of the Federal Government continuously harried and implicitly threatened Facebook with potentially crippling consequences if it did not comply with their wishes about the suppression of certain COVID–19-related speech,” Alito wrote. “Not surprisingly, Facebook repeatedly yielded. As a result, Hines was indisputably injured, and due to the officials’ continuing efforts, she was threatened with more of the same when she brought suit.”

Alito concluded the court’s majority shirked its responsibility to defend the public from censorship instigated by the federal government: “It was blatantly unconstitutional, and the country may come to regret the Court’s failure to say so.” The dissenters are right. The majority indulged in excessively cute reasoning to avoid a hot political issue.

Overall, the Supreme Court made significant progress this term toward restoring the nation’s constitutional structure. It emphasized separation of powers and the rights of states and people to govern themselves without federal interference in areas outside the Constitution’s authority. This is an extraordinary and unexpected development of historical significance.

Read the full article here

![Race-Based Questions Shut Down by Notre Dame Coach Marcus Freeman After Historic Win [WATCH] Race-Based Questions Shut Down by Notre Dame Coach Marcus Freeman After Historic Win [WATCH]](https://www.lifezette.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/01/2025.01.10-08.06-lifezette-67817dd7a1932.jpg)

![‘Fiddling’ During DEI Green New Deal Chaos [WATCH] ‘Fiddling’ During DEI Green New Deal Chaos [WATCH]](https://www.lifezette.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/08/2024.08.23-01.19-lifezette-66c88c7bdcbfb.jpg)