No political insult gets thrown around more recklessly these days than “fascist.” The word has been gutted of meaning, reduced to a club progressives swing at President Trump and people like Stephen Miller and the late Charlie Kirk. Democrats and their media allies casually smear conservatives as extremists who follow the “fascist playbook.”

Joe Biden himself dragged the rhetoric to a new low. In September 2022, standing in front of Liberty Hall in Philadelphia, he declared that “MAGA Republicans” are extremists and enemies of democracy.

“They embrace anger,” Biden thundered. “They thrive on chaos. They live not in the light of truth, but in the shadow of lies.” Weeks earlier, at a fundraiser in Maryland, he even called the MAGA movement “semi-fascist.”

The smear reveals less about conservatives and more about the authoritarian streak buried in the left’s own philosophy.

Say what you want about Trump’s sharp elbows in politics, but he never demonized American voters as enemies of the republic. Biden did — and Democrats have repeated the smear ever since. The question is: What happens to a country when its leaders brand millions of citizens “fascists”?

The goals of the MAGA movement are plain: Protect natural rights, foster prosperity, expand energy access, secure the border, reduce crime, preserve domestic peace, and pursue a foreign policy rooted in prudence. These aims hardly resemble fascism. Yet defenders of liberty now find themselves caricatured as authoritarians.

To see how absurd this charge is, it helps to remember what fascism actually means.

A (very) short history of fascism

The intellectual father of fascism was Giovanni Gentile, an Italian philosopher born in 1875. Following Hegel, he saw the rational state as the end point of history. He defined “true democracy” not as liberty but as the individual’s willing subordination to the state.

For Gentile, public and private interests were one and the same. To serve society was to serve the state. His student, Benito Mussolini, turned this philosophy into doctrine: “All is in the state, and nothing human exists or has value outside the state.”

Contrary to today’s rhetoric, fascism did not begin on the right. Mussolini himself was a Marxist. He and Antonio Gramsci broke with Leninist revolution but retained socialism’s collectivist core. Fascism emphasized nationalism, racial particularity, and the total authority of the state — summed up in the term “blood and soil.” Its very name came from the Latin word fasces, the Roman bundle of rods bound to an axe — symbolizing unity and power.

Fascism arose in the economic chaos of the 1920s and ’30s. Italy and Germany launched massive public-works programs, funded by confiscatory taxes, borrowing, and printing money. As with communism, fascism treated every citizen as an employee and tenant of the party-run state. Force and coercion were essential. Mussolini was blunt: The individual’s “anti-social right” to resist the state did not exist.

In his 1928 autobiography, he wrote:

The citizen in the Fascist State is no longer a selfish individual who has the anti-social right of rebelling against any law of the Collectivity. The Fascist State with its corporative conception puts men and their possibilities into productive work and interprets for them the duties they have to fulfill.

Fascism and the New Deal

The American version of the 1930s response to the Great Depression, of course, was Franklin Roosevelt’s New Deal. Today it’s remembered as democracy’s answer to authoritarianism. But at the time, many noted striking similarities between Roosevelt’s programs and those of Mussolini and Hitler.

John T. Flynn, a leading conservative writer, warned in “As We Go Marching” (1944) that the New Deal looked like a “good fascism” — regulation and planning at home, military adventures abroad, and growing state power. Others saw the same trend: massive public-works projects, charismatic leadership, centralized propaganda, and the creation of a “voluntary compulsion” that blurred the line between civic duty and government coercion.

Wolfgang Schivelbusch’s remarkable 2006 book, “Three New Deals,” compares the era’s regimes. He did not equate Roosevelt with Mussolini or Hitler, but he highlighted the parallels: grand projects like the TVA, monumental architecture, direct appeals from the “leader” to the people, and the constant use of war imagery. Roosevelt even warned that those who resisted his programs were “enemies” of recovery.

The difference, of course, was that America retained constitutional checks that Europe discarded. Yet the centralizing impulse — and the temptation to vest extraordinary authority in a leader — was real.

Progressive roots

The resemblance should not surprise us. European fascism and the New Deal both grew from the same philosophical soil. The American founding drew on John Locke and natural law. “The state of nature has a law of nature to govern it, which obliges every one,” Locke wrote. “And reason, which is that law, teaches all mankind.” The Declaration of Independence, in turn, proclaimed that rights are endowed by the Creator and cannot be erased by government.

European thought took another path, from Machiavelli to Hegel, exalting the state as the source of order and authority. By the late 19th century, American Progressives imported this vision. Woodrow Wilson and other intellectuals trained in German universities rejected the founders’ natural-rights philosophy and embraced statism.

RELATED: The next generation of Marxists is marching through the institutions

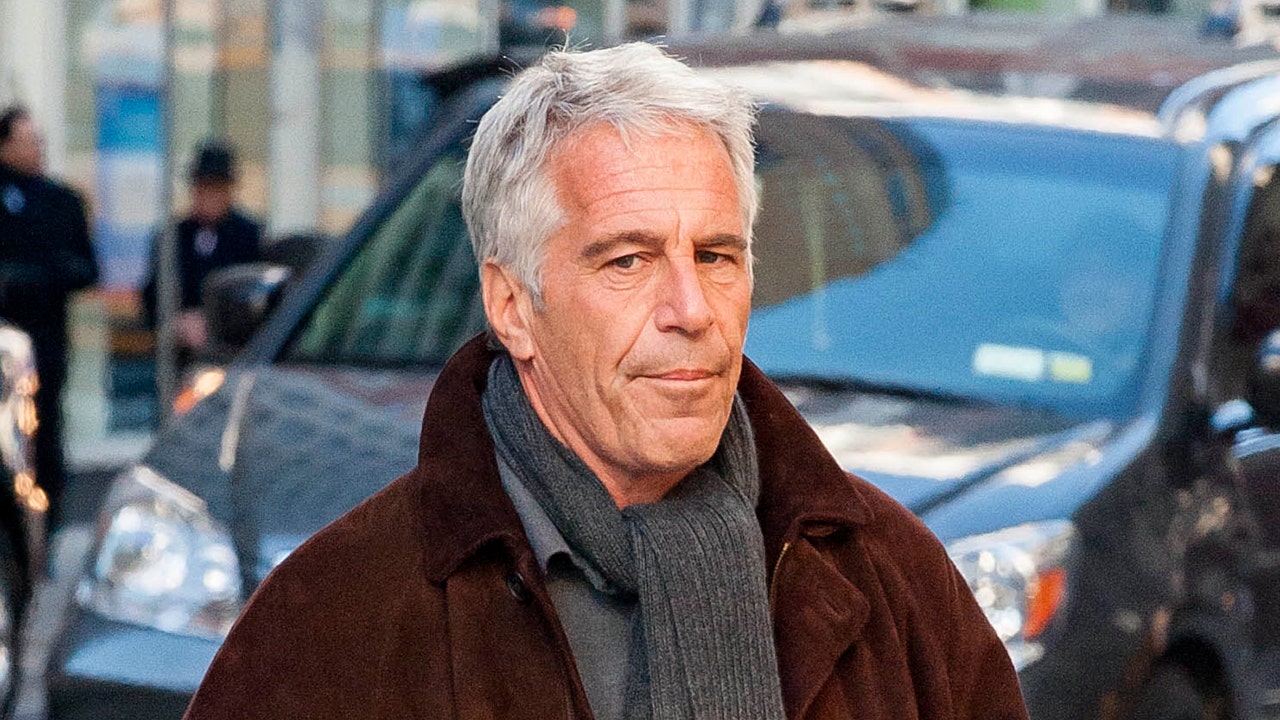

Photo by Luiz C. Ribeiro for NY Daily News via Getty Images

Progressives, like their European cousins, placed the state at the center of political life. They taught that rights flow not from God but from government — positive, material entitlements dispensed by bureaucrats. Over the past century, Democrats from Wilson and FDR to Lyndon Johnson and Barack Obama have built a regime that subordinates every aspect of American life to the federal leviathan.

The real irony

Given this history, 21st-century progressives should think twice before flinging “fascism” as a slur. Their own intellectual lineage shares far more with Mussolini and Gentile than anything found in the MAGA movement.

Trump supporters want liberty secured, prosperity restored, and sovereignty defended. Progressives want the state elevated above all. The smear reveals less about conservatives and more about the authoritarian streak buried in the left’s own philosophy.

Read the full article here

![Schumer’s Shutdown Begins as 45 Democrats Vote To Give Illegal Aliens Health Care [WATCH] Schumer’s Shutdown Begins as 45 Democrats Vote To Give Illegal Aliens Health Care [WATCH]](https://www.lifezette.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/10/2025.10.01-10.40-lifezette-68dd0532b442f.jpg)

![Kash Patel Applauds Dan Bongino’s FBI Work, Bongino Responds [WATCH] Kash Patel Applauds Dan Bongino’s FBI Work, Bongino Responds [WATCH]](https://www.rvmnews.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/07/2024.07.27-04.09-rvmnews-66a51bd38ecd3.jpg)