Ready the lawyers! You better believe that Lee Zeldin has already mobilized the EPA’s legal department in anticipation of exactly this fight.

Donald Trump campaigned on rolling back regulatory intrusions on American production, especially in energy and manufacturing. Zeldin will follow through on that promise by aiming to end the EPA’s 2009 “endangerment finding” that expanded the EPA’s reach on ‘climate change’-related activities. Zeldin promised to do that as soon as he got confirmed as EPA Administrator, and Axios reports that Zeldin will launch that effort very soon:

EPA Administrator Lee Zeldin said Tuesday he’s issuing draft plans to overturn the agency’s 2009 scientific finding that greenhouse gases threaten human health and welfare — a move guaranteed to spark litigation.

Why it matters: It’s President Trump’s most direct effort to rip out climate regulations root and branch — and make it harder for a successor to impose new ones.

- The “endangerment finding” provides a key legal underpinning for regulating heat-trapping gases from cars, power plants and more under the Clean Air Act.

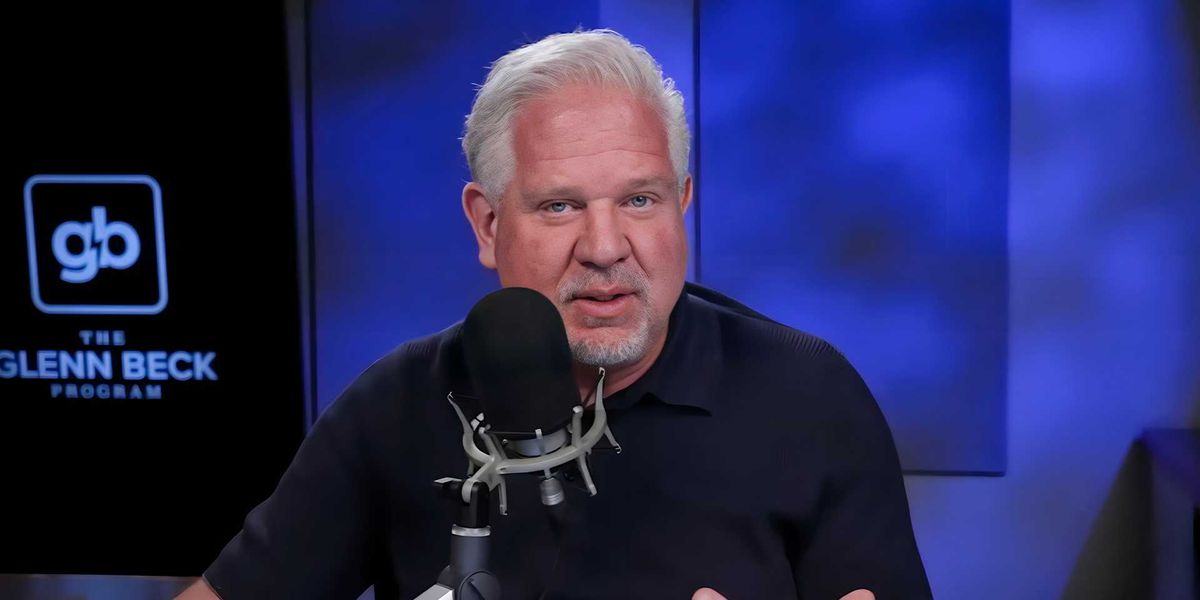

Driving the news: “This has been referred to as basically driving a dagger into the heart of the climate change religion,” Zeldin said on Ruthless, the popular conservative podcast where he announced the plan.

To understand the import of Zeldin’s action, it’s important to recall how the EPA created this “endangerment finding” in the first place. Activist groups sued the EPA to force them to classify ‘greenhouse gases’ as pollutants for the purpose of regulation. The Clean Air Act allowed the EPA to do so, but Congress did not require it in the statute. The Supreme Court ruled in 2007 in a 5-4 decision that experts mean more than statutes, and allowed the lawsuit to continue. At the time, Justice Antonin Scalia was astounded:

The question thus arises: Does anything require the Administrator to make a “judgment” whenever a petition for rulemaking is filed? Without citation of the statute or any other authority, the Court says yes. Why is that so? When Congress wishes to make private action force an agency’s hand, it knows how to do so. See, e.g., Brock v. Pierce County, 476 U. S. 253, 254–255 (1986) (discussing the Comprehensive Employment and Training Act (CETA), 92 Stat. 1926, 29 U. S. C. §816(b) (1976 ed., Supp. V), which “provide[d] that the Secretary of Labor ‘shall’ issue a final determination as to the misuse of CETA funds by a grant recipient within 120 days after receiving a complaint alleging such misuse”). Where does the CAA say that the EPA Administrator is required to come to a decision on this question whenever a rulemaking petition is filed? The Court points to no such provision because none exists. …

“While the statute does condition the exercise of EPA’s authority on its formation of a ‘judgment,’ … that judgment must relate to whether an air pollutant ‘cause[s], or contribute[s] to, air pollution which may reasonably be anticipated to endanger public health or welfare.’ ” Ibid. True but irrelevant. When the Administrator makes a judgment whether to regulate greenhouse gases, that judgment must relate to whether they are air pollutants that “cause, or contribute to, air pollution which may reasonably be anticipated to endanger public health or welfare.” 42 U. S. C. §7521(a)(1). But the statute says nothing at all about the reasons for which the Administrator may defer making a judgment—the permissible reasons for deciding not to grapple with the issue at the present time. Thus, the various “policy” rationales, ante, at 31, that the Court criticizes are not “divorced from the statutory text,” ante, at 30, except in the sense that the statutory text is silent, as texts are often silent about permissible reasons for the exercise of agency discretion. The reasons the EPA gave are surely considerations executive agencies regularly take into account (and ought to take into account) when deciding whether to consider entering a new field: the impact such entry would have on other Executive Branch programs and on foreign policy. There is no basis in law for the Court’s imposed limitation.

Two years later, the Obama-era EPA issued its ‘endangerment finding’ in the settlement of the lawsuit, a favorite strategy for forcing policy changes through courts rather than legislatures. The EPA did have this authority, and Barack Obama almost certainly would have pursued it regardless of the decision in Massachusetts v EPA. The point of the lawsuit was to force a Republican administration into enforcement of progressive-left policies on global warming, and the Supreme Court at that time went along with it, led by Justices John Paul Stevens and Anthony Kennedy.

That brings us to today, and what the Trump administration wants out of this fight. Technically, Massachusetts v EPA still controls this question, and any attempt by the EPA to vacate its endangerment finding and end regulation of so-called greenhouse gases will get challenged on that precedent. However, today’s Supreme Court is much different than the 2007 court, and has grown far more skeptical about “expert” technocratic rule. While Chevron isn’t directly implicated in Massachusetts v EPA, its underlying trust in experts runs rampant in Stevens’ controlling opinion. (Ironically, Scalia cited Chevron four times in repeatedly asking why the EPA was not given due deference for its decision to decline regulation of greenhouse gases.)

The legal fight is the goal behind Zeldin’s upcoming action. The Trump administration wants a do-over on Massachusetts v EPA to get rid of the climate-change mandate in the short run. They may want an even broader decision that seriously impedes, if not entirely stamps out, the regulation-by-litigation cycle. This court has already overturned Chevron in the context of interpreting regulatory decisions, and at the same time has created precedents that force consideration of “major questions” to Congress rather than district court judges and unelected bureaucrats at regulatory agencies. The court has belatedly taken Scalia’s wisdom to heart in his dissent in Massachusetts v EPA when he pointed out that Congress knows how to create statutory requirements for regulation when it sees the need.

Zeldin has to take his time and ensure that this process follows all of the Administrative Procedue Act rubrics. It won’t help matters to rush this effort and produce a sloppy record that gives district court judges a technicality to reverse this effort rather than address it on the merits. If successful, this will give Trump another step in recovering his constitutional executive authority and force legislative activity back to Congress rather than abdicating it to special interests and the plaintiff’s bar. And that is a reform that is very much overdue.

Also, the latest episode of The Ed Morrissey Show podcast is now up! Today’s show features:

- Has Stephen Colbert rung the curtain down on a genre that stretches back to the start of television?

- Andrew Malcolm and I discuss what made it work for Johnny and Jay, and why the genre is doomed in the era of Regime Comedy.

- We also discuss a much-needed rethinking of Barack Obama’s legacy, and why Donald Trump’s trade success confounds both Democrats and the media.

The Ed Morrissey Show is now a fully downloadable and streamable show at Spotify, Apple Podcasts, the TEMS Podcast YouTube channel, and on Rumble and our own in-house portal at the #TEMS page!

Editor’s Note: Every single day, here at Hot Air, we will stand up and FIGHT, FIGHT, FIGHT against the radical left and deliver the conservative reporting our readers deserve.

Help us continue to tell the truth about the Trump administration and its successes. Join Hot Air VIP and use promo code FIGHT to get 60% off your membership.

Read the full article here

![CNN’s Harry Enten Bursts Liberal Bubble, Debunks ‘Losing His Base’ Claims [WATCH] CNN’s Harry Enten Bursts Liberal Bubble, Debunks ‘Losing His Base’ Claims [WATCH]](https://www.lifezette.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/07/2025.07.29-08.27-lifezette-688885e4b28f7.jpg)

![Trump Makes Major Move Against Minnesota Somalis in Wake of Massive Fraud Scandal [WATCH] Trump Makes Major Move Against Minnesota Somalis in Wake of Massive Fraud Scandal [WATCH]](https://www.lifezette.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/11/2025.11.22-01.09-lifezette-6921b6030b5f7.jpg)

![Supreme Court Blocks Judge’s Order Tossing Texas Redistricting Maps [WATCH] Supreme Court Blocks Judge’s Order Tossing Texas Redistricting Maps [WATCH]](https://www.lifezette.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/04/2025.04.21-09.15-lifezette-68060c9d4995e.jpg)